WE WERE SAILORS

WE WERE SAILORS

by William Thomas

Lifted gently off the beach by dawn’s small tide, the raft bumped against the legs of her handlers straining at each corner. In later years, no spaceship launched from Cape Canaveral would be attended as avidly as this first attempt by Homo sapiens to reach a distant shore.

They knew what they were doing. Modern humans had fished for millennia from small rafts bobbing on South African lakes. As unglimpsed northern icefields continued to recede over the past 10,000 years, logs laboriously recovered from rainforests surging beneath a newly trending warm, wet southern climate substituted for the absence of bamboo. As a result, this 60-hands-long oceangoing prototype weighed as much as a small elephant. When completed, the small band rallied to push the beach-assembled raft over log rollers three-meters to the low tide mark. Would Shearwater skim the sea like her namesake, or… ?

“Bad name,” little Slow Runner solemnly pronounced. “Not bird. Hippo.” She giggled.

“Shut up,” said her brother, giving her a poke.

Detaching himself from the crowd, a tall hominid called Urg waded around the gently bobbing creature that had consumed so much of their time, treasure and talent. Casting a practiced eye over the 30-foot raft, the band’s leader and best fisher tugged at the palm frond lashings. Satisfied, he returned to shore. Reaching into a bead-decorated pouch, Urg withdrew a small handful of sand carried all the way from northern deserts. Opening his fingers, he loosed the talcum-fine powder. No breeze disturbed its fall. Even the sea was still, as if shocked by their audacity.

The band’s boss nodded. Murmurs grew to an excited hum as six paddlers swarmed aboard the raft. The chief’s son took his place to call instructions. Sees Far called out and the kneeling paddlers dug hard into the low swell. Someone started the fish song, and soon all were chanting in unison to synchronize their stroke.

Across the strait – perhaps the distance of a morning’s ramble by grazing wildebeest – beckoned faint grey slopes. Made indistinct by haze, whatever promise and perils awaited, the far shore held out one overriding attraction: no other footprints could have disturbed that as yet unglimpsed beach.

The band was in trouble. Under the press of immigrants from the drying north and a baby boom sparked by abundant seafood here, the tribes occupying this stretch of Africa’s bulging east coast had surpassed 150-members – the maximum number of relationships modern brains could manage. Bands were splintering off. And many of these 40 to 50-member groups found themselves in steepening decline. As bunches of fresh provisions, drinking coconuts, fishing gear, favourite tools, spare lashings, a fire-making drill and dry tinder wrapped in palm leaves were quickly stowed onboard, food was clearly not yet an issue.

But competition for available females was steadily eroding this small company as eligible females sought polygynous relations with single men from other bands. Or were simply stolen. The latest aggressive displays amongst their own extended clan had been acrimonious nearly to the point of bloodshed.

If the raft’s innovative pinched, upswept ends performed well Urg thought. If wind and seas do not rise. If they survive multiple crossings to ferry their infants, surviving toddlers and remaining females safely across, the band’s survival would be assured. At least for a time. But if the raft founders and they lose their seven strongest men, the band will never recover.

Everyone fell silent. At a distance of an atlatl throw, the paddlers reversed their stance and headed back toward shore. Standing apart, the clan’s bone-and-bead-bedecked old shaman – already in his late-thirties – narrowly gauged how the raft with her odd upswept bows took the sea. Extending his right arm straight out, he held his hand on-edge. If turned palm down, the cursed conveyance would be burnt on the beach.

As the craft grounded on the sand, every gaze focused on that signal. In the sudden hush, even Slow Runner fell silent. The shaman rotated his hand… palm up. And smiled. . . .

“Stay down!” hissed the guide, lying prone with her paying charge in tall grass atop the bluffs behind the beach. “Don’t move. If they see us…”

She did not have to spell out the penalties for time-travelers who disturbed the local fauna.

“When are we?” said the self-appointed blowhard in a voice better suited to a noisy pub.

Amethyst consulted her modified Seiko. “We’re 125,000,” she whispered. “Years BP. Before Present."

The idiot would have whistled if she hadn’t glared at him. Instead, he made big eyes, “We were making deliberate open sea passages that long ago?

How far across?”

“Not quite four-and-a-half nautical miles.”

“Nautical who?”

“Eight kilometers.

Their timing is good. After the ice age finishes melting down, sea-levels will rebound, resulting in a 32-kilometer crossing today.” “Four miles? That all?” His snort sounded like a braying zebra. Totally out of place on this beach.

“Keep it down,” she hissed. “Let me assure you that two-and-half miles offshore is a very big deal. When was the last time you were that far from dry land, onboard a waterlogged raft working its lashings loose in a seaway?”

“Water over my head freaks me out.”

“With no human precedent and little indication of what lies ahead, that crew is facing hours of precarious exposure. Did I mention unforeseen currents and sudden storms sweeping them into the vastness of the Indian Ocean? Even light adverse headwinds would have kept return runs beached or forced any raft already at sea to turn back.”

“You said they knew what they were doing.”

“It’s true they are well-versed in raft technology. And thanks to their aquatic-adapted ancestors, they feel at home in – and on – the water.”

“But…”

“But like any boat, rafts don’t simply upscale from smaller models. And the open ocean, with a fetch of thousands of miles, will take their experience on sheltered lakes to an entirely new realm.”

“So, they’re like prehistoric astronauts. Argonauts.”

“Keep still and watch. Seven Huck Finns are about to set out upon the open sea for the first time in the Homo sapien saga.”

“Across the Gate of Grief.”

She was almost impressed. After putting down two-million New Yuan on today’s excursion, he’d actually read the brochure.

WATER-BABIES

Traveling, making the world go past and arriving someplace new, is humanity’s earliest and most enduring propensity. For something like seven million years since the first hominid prototypes split from chimpanzees in a climate-buffeted crucible we now call Africa, we have remained restlessly, ceaselessly on the move. From humanity’s earliest beginnings, the sea covering more than two-thirds of this waterworld was our longest, boldest highway.

Who can resist that call? Not us water-babies. Not when Mother Ocean tugs at us in salty sperm, amniotic tides, blood and tears. Not when our pre-human predecessors were by necessity aquatic.

“It seems that Man learned to stand erect first in the water,” insisted marine biologist, Sir Alister Hardy – pointing to Ethiopian apes cut-off by periodic and persistent inundations that were forced to become waders to reach once-convenient fruit now hanging low over waist-high water. As these apes became more human, they became the only species in which fur gave way to naked flesh – to facilitate swimming, argues Elaine Morgan in The Aquatic Ape Hypothesis, a book more mind-altering than LSD. Naked Ape author Desmond Morris also believes an aquatic phase of human development is “highly likely.”

Like contemporary human infants birthed happily underwater, H. erectus would have felt at home in the water. Which helps explain why eons before horses, horsepower and wings turbocharged our wanderlust, venturing out on the ocean aboard homemade seacraft was humanity’s first and most formative feature.

OUT OF AFRICA (MORE THAN ONCE)

On a continent shaped like knapped flint, with eastern exits ruled by persistent wet and dry periods caused by Earth’s metronomic orbital fluctuations, some 3 to 3.5 million years ago there were no Saharan–Arabian desert barriers to egress from North Africa. As a result of these salubrious circumstances, “hominids were distributed throughout the woodland and savannah belt from the Atlantic Ocean across the Sahel through eastern Africa to the Cape of Good Hope,” traces Rajeev Patnaik from Panjab University.

Following game and their own curiosity, opportunistic hominins of the human lineage “migrated into Eurasia at about 2 million years ago, or even earlier.” When subsequent favourable climate shifts opened brief “green corridors” between Africa and Arabia and the eastern Med, now-extinct ancestors to modern Homo sapiens roamed vast areas of China as early as 1.7 million years ago. In one locale, 90 miles west of present-day Beijing, thousands of discarded tools litter 60 Stone Age sites. Around the same time, hominins also established an abortive colony in Dmanisi, Georgia.

These groups – and others like them – possibly evolved from tool-making, habilis-like ancestors who had previously wandered out of Africa without even knowing they had left. More likely, according to archeology’s latest revision, H. ergaster, H. erectus and H. georgicus belonged to the same species with startlingly different traits – the incredibly durable and far-ranging Homo erectus. Time, as cosmologists like to say, passed…

DEPARTING DODGE

Back in South Africa, by 164,000 BP early modern humans had fled northern climes afflicted by encroaching drought to settle in luxurious condo-caves at scenic Pinnacle Point on the Cape of Good Hope. Table scraps show these early humans living the good life just around the corner from that deep sea gateway into Arabia. But Aladdin's fabulous continent was accessible only by floating carpet. For millennia, each band stayed focused on dinner, not the Stone Age equivalent of space travel. Pre-packaged in handy steamer shells, the beachcombers’ favourite food – brown mussels – lay exposed at low tide right below their panoramic living rooms.

According to the archaeological record, everything looks picture-book perfect for another 100,000 years or so, until the Earth teeters once again in its passage around the sun and a prolonged drought in north Africa, Saudi and the eastern Med sends climate refugees fleeing south onto Africa’s south coast some 60,000 years ago. The hungry interlopers helped motivate the scowling locals, who, as Mascarelli puts it, “got out of Dodge.”

Trekking north into the expanding Arabian desert “would have been a bad choice,” cautions Axel Timmermann, a U. of Hawaii climate scientist and lead author of a major Paleo-African climate study. “Modern humans could not have taken a northern route prior to 50,000 years ago,” clarifies National Geo’s Hillary Mayell, because the planet was gripped by the first half of the last ice age and “the whole of North Africa, Arabia, and the Middle East into Central Asia was desert.” Arm-waving new arrivals at Pinnacle Point would have made that clear.

GO EAST, YOUNG HUMANS

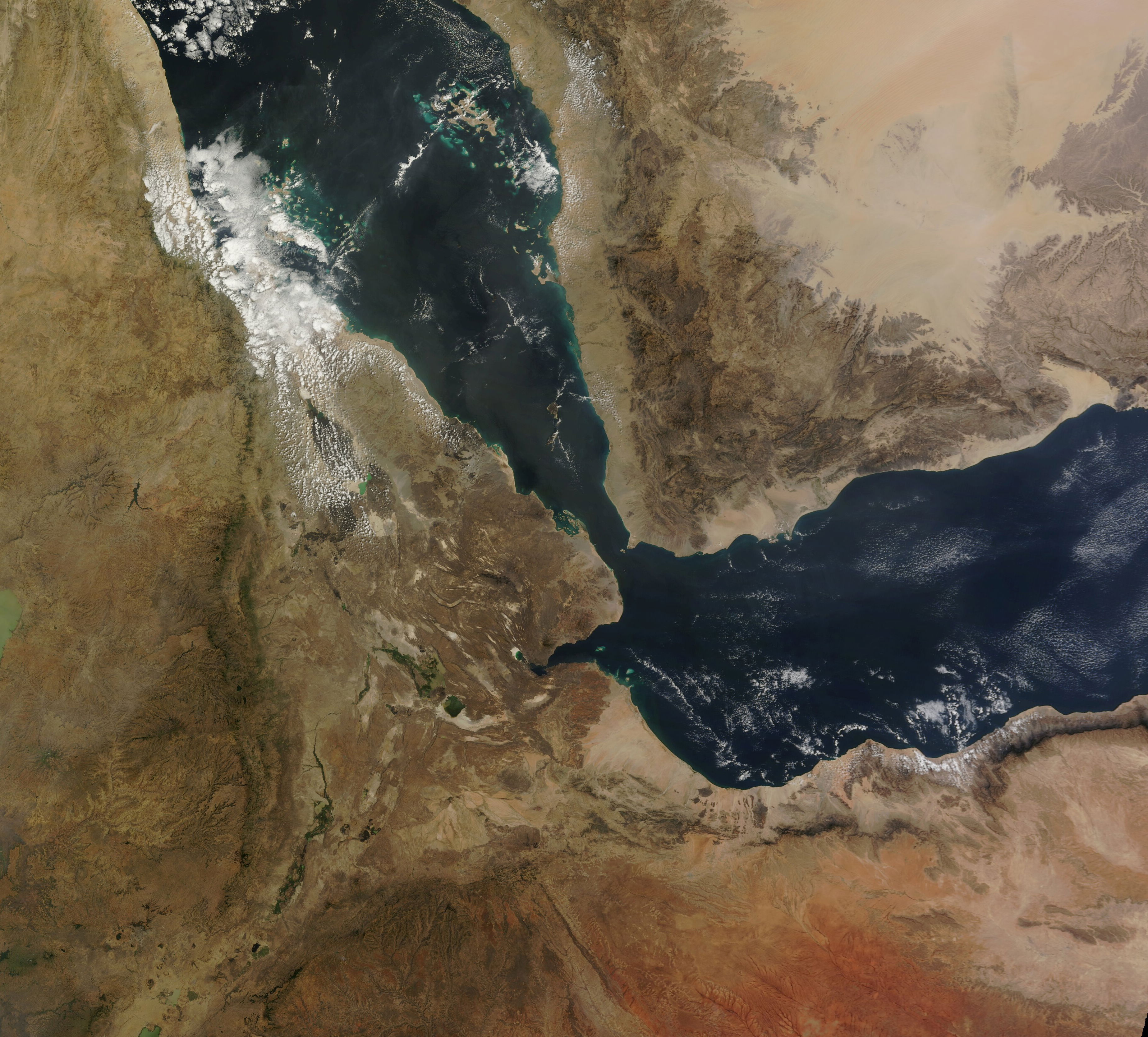

Confronted by a then-impassable desert to the north, or an open sea passage across the later renamed Gate of Tears at the mouth of the Red Sea, for an animal both cursed and blessed by a neocortex, our ancestors’ choice was a no-brainer. Hans-Peter Uerpmann of Germany’s U. of Tübingen says the southern sea road across to Arabia "is more plausible for massive movements than the northern route" up through arid Saudi Arabia and Egypt. In fact, adds Martin Robinson, “a six-year study mapping genetic patterns found that people who ended up in Europe, Asia and Oceania got there by crossing the sea to Arabia around 70,000 years ago, when sea levels were low enough for people to cross from the horn of Africa into Arabia via the Bab-el-Mandeb.”

How low? Around 10,000 years ago, the glacier-shrunken strait narrowed to just 2.5 miles across.

“They couldn’t have simply caught a ride on a floating log because then they would have been washed out to sea when they hit the current,” points out Daniel Everett, professor of global studies at Bentley U. The prehistoric mariners also had to make return ferry trips to get bands and clans across. Which means, Everett adds, “They needed to be able to paddle. And if they paddled they needed to be able to say ‘paddle there’ or ‘don’t paddle.’ You need communication with symbols, not just grunts.” And so, we became sailors. Why not? Long before our officially time-stamped human beginnings, we were travelling distant seas.

DISPERSAL

This first exodus across the Red Sea to the Arabian coast was not a single event, reiterates Axel Timmermann. Instead, these “Out of Africa” migrations occurred in waves as Earth’s wibble-wobble caused abrupt and prolonged wet-and-dry “shifts in climate and vegetation in tropical and subtropical regions.”

Humans with attitude traveled out of Africa in at least four long diasporas, Mascarelli mentions. Those waves “occurred from 106,000 to 94,000 years ago, 89,000 to 73,000 years ago, 59,000 to 47,000 years ago, and 45,000 to 29,000 years ago – results that align well with a growing body of archaeological and fossil [and genetic] data.” The penultimate embarkations of foraging-and-hunting bands crossed the Bab-el-Mandeb as recently as 60,000 years ago. By then, sea levels were 230 feet lower than today, locked up in continent-crushing ice caps that discouraged further rambles into northern Europe. Have respect for their achievement. Those are your folks building and paddling those first seagoing rafts.

BOTTLENECK

"The initial dispersals out of Africa prior to 60,000 years ago were likely by small groups of foragers, and at least some of these early dispersals left low-level genetic traces in modern human populations,” explains Michael Petraglia of the Max Planck Institute for the Science of Human History. Most of those pioneering bands died out, as the strait of Bab-el-Mandeb proved to be a population bottleneck.

Dr. Stephen Oppenheimer, a geneticist at the school of anthropology at Oxford University who has led research on the genetic origins of humans outside Africa, explains: "What you can see from the DNA of all non-Africans is that they all belong to one tiny African branch that came across the Red Sea.”

One twig survived from all that hominid shrubbery.

“Geneticists and archaeologists trace the origins of modern homo sapiens back to a single group of people who managed to cross from the Horn of Africa and into Arabia. From there they went on to colonise the rest of the world,” picks up Richard Gray. It was a near-run thing. “The entire human race outside Africa owes its existence to the survival of a single tribe of around 200 people who crossed the Red Sea 70,000 years ago.”

"The founder populations cannot have been very big. We are talking about just a few hundred individuals," concurs Dr. Peter Forster after carrying out genetic mapping in Cambridge. Genetic diversity among modern individuals reveals that an earlier population bottleneck threatened the Homo sapiens experiment in migrations out of Africa some 100,000 years ago.

WHEN HUMANS WEREN’T QUITE HUMAN

If the notion of your distant grandparents risking their necks and your future existence on an open water crossing 125,000 years ago hurts your brain, you’d better grab your head with both hands. Because those early humans were following in the wakes of their pre-human predecessors. To all you ladies and gentlemen (and those still deciding), I present the world’s very first, number one, genuine original, seagoing almost-humans: Homo erectus!

These upright, anatomically-refined, post-chimp/pre-Homo sapiens were a restless lot. Utilizing a brain half-again bigger than much earlier Australopithecus, erectus developed bluewater technologies using tools far removed from the crude sharpened stones and pounders used by chimps, “Lucy” and other pre-humans 3.3 million years ago.

PREHISTORIC PROMISCUITY

Stop making fun of Neanderthals. For one thing, the long-enduring Neanderthals shared our own “language gene,” FOXP2. For another, as our “erect” ancestors crisscrossed continents, “they would have encountered a motley assortment of other archaic human species, including the Neanderthals in Eurasia, the Denisovans in Siberia,” reports Science correspondent Hannah Devlin – as well as Hobbits marooned on an Indonesian island – “and probably other species that we do not yet know about.”

Forget the fabled “missing link” and your engraved invitation to the “birth” of modern humans. With “human” anatomical traits ricocheting back-and-forth between various evolutionary offshoots, our “family tree” emerging from this prehistoric Peyton Place reminds Science’s Hannah Devlin, is “more like a dense, thorny bush.” Most of these first European explorers “eventually faded away” sighs Amanda Mascarelli.

YO MAMA

Nature’s blind imperative to breed or perish never anticipated our modern machine-amplified impacts. Or our eventual numbers. But evolution does make racism ridiculous. From “white” supremacists to Arab-hating Zionists oblivious to their own anti-Semitism, everyone’s original mom was a black Ethiopian.

We’re also part Neanderthal. “Interbreeding between modern humans and Neanderthals means that all non-Africans alive today carry about 1-5% Neanderthal DNA,” Devlin explains, “so collectively there is a substantial fraction (at least 20%) of the Neanderthal genome spread through the living human population.”

Our ancestors got it on with other species?

“The ancestors of everyone outside of Africa interbred with Neanderthals, probably more than once. There was also interbreeding with another archaic group called the Denisovans,” Devlin devilishly declaims. “The Earth was once home to a surprising diversity of humans, some of whom crossed paths with our own ancestors.” Regardless of your location or pigmentation, why should all this… ahem… activity matter to you? You’re here.

DID YOU SAY SOMETHING?

As Adam’s Tongue and The First Word explain at length, somewhere along the way, Homo habilis started making meaningful sounds. Homo erectus developed this proto-language into a culturally–transmissible idiom – an essential skill for boatbuilders, navigators and anyone who spots a shark. Observes Kevin Laland, professor of Behavioural and Evolutionary Biology at U. of St Andrews: “It would have been very difficult for knowledge of how to manufacture Homo erectus’ Acheulian stone tools to spread without a simple form of language.”

Sporting thick brow ridges and a supercharged 1225cc brain (vis our own pelvis-stretching 1500cc model), our precocious predecessors captured fire and became chefs, leaving ashes and charred bone in clan-size Wonderwerk Cave, a massive cavern located near the edge of today’s Kalahari Desert. As Charles Q. Choi reports for Live Science, “the earliest known evidence of controlled use of fire” took place one-million years ago. Think about that the next time you fire up your barbie* to char an oryz.

HOMO BOOGEYING ERECTUS

Unaware that they “weren’t fully human,” Homo erectus is considered the first cosmopolitan, Devlin declares, “due to the impressive geographical range it spanned, with fossils found in Africa, Spain, Italy, China and Indonesia.”

How did old Homo erectus get to all those far-flung places?

By water, of course. Turns out – and a squawking flock of landbound anthropologists are extremely unhappy over these extensive archaeological findings – upright, bipedal erectus made the first intentional open-water crossings, out of sight of shore, nearly one-million years ago.

You read that right. And maybe you’ve read Bednarik’s landmark book, The First Mariners. So, go ahead and challenge the dock committee at your yacht club bar to guess when their not-quite-fully-human ancestors first fetched distant landfalls in Stone Age craft, through the current-swept Indonesian archipelago all the way to Australia – you're going to need them.

Photo Captions:

Tamil log raft

Bab el Mandeb from space

Bab el Mandeb strait of Somalia.

Rose putting finishing touches on her paddle -P. Farrance

*The proper name for “barbecue”. Given how long ago the first sailors reached Oz, we should, out of respect (or just for fun), all be speaking Aussie.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR For eight years and 40,000 sea-miles aboard their backyard-built trimaran, Celerity... photojournalist William Thomas and his mate, Thea sailed in quest of the last great sailing double-canoes, proas and junks across Polynesia, Micronesia, Hong Kong and China.

And found them.